Your cart is currently empty!

Guide to Fertilizing Vegetables

Get updated by email whenever there’s a new post

Soil fertility and nutrient availability combined with air and water are essential for growing a garden. They give us life.

For plants to feed us, they not only need a lot of the non-mineral elements Carbon (C) , Hydrogen (H), and Oxygen (O), they also need many other mineral nutrients. Seventeen total minerals are needed, and the 14 mineral nutrients are broken down into macronutrients or micronutrients. This nomenclature simply denotes how much of the element is required for plant growth.

Primary macronutrients are nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). These are the NPK denoted on fertilizers such as a 10-10-10, equal parts of each.

Then there are secondary macronutrients: Calcium (Ca), Magnesium (Mg), and Sulfur (S).

Finally, trace elements are also needed, though in smaller amount still. This group is comprised of Boron (B), Copper (Cu), Chlorine (Cl), Iron (Fe), Manganese (Mn), Molybdenum (Mo), Nicket, and Zinc.

Plants primary form of nutrient uptake is through the soil. In organic gardening, these nutrients are most often supplied in an unavailable form that microbial fungi and bacteria convert into usable form over time. Top dressing with compost — adding organic matter to the soil — and using a slow release organic fertilizer are my top tried and true ways to deliver nutrients for the microbes to metabolize (it’s a process called mineralization).

The Importance of Soil pH

But just because we supply the soil microbes with the nutrients doesn’t mean it will work. The other major factor in nutrient uptake is soil pH. The pH of your soil can be obtained through a soil test. It’s the first thing we did with our site when we built our raised beds (though we haven’t re-tested since fall of 2016).

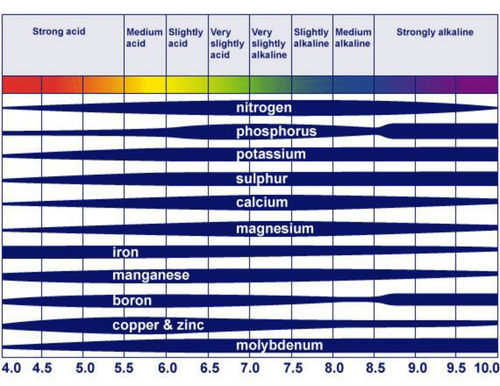

If your pH is too high or too low essential nutrients will be locked up and unavailable, no matter how much fertilizer you add to the soil. A pH around 7 (6.0 – 7.5) is generally a good level for growing food, except for blueberries, lingonberries, and cranberries which prefer moderately acidic soils. For those unusual plants, we amend with peat moss at planting and add elemental sulfur annually to maintain a lower pH.

If you don’t know your soil pH definitely look up your state’s extension agency and get your soil tested.

This is our soil test results from fall of 2016. This is straight up dig up some turf and see what the soil reads, before we added compost or anything else to our soil to improve drainage.

As you can see, our Phosphorus is really high. That is in part due to the previous owner’s love of turf grass. Phosphorus is rather immobile and so it ends up accumulating in the soil.

I’ve been learning about the fact that Phosphorus is needed much less than say Nitrogen (extension papers cite a 4:1 Nitrogen to Phosphorus need). So it is with some curiosity I might try mixing up our next batch of fertilizer without any rock phosphate.

Another possibility would be to just add soybean meal or another seed meal to our garden beds every year. It might be all we need due to our rich in organic matter soil, but I am not sure I’d be able to jump off that cliff with any modicum of confidence and without some serious sleep deprivation ensuing. But maybe one day I’ll be brave enough to try. We may be feeding our soil too much, but then again our plants seem to love the approach we are taking so it’s hard to convince me to change.

Slow Release vs Foliar Feeding

We have options for applying fertilizers, and it might be a bit confusing. I know I can get confused and overwhelmed, even in researching this post.

In simplest terms, you want to feed your soil microbiome in order to feed your plants. Here in our gardens and for as long as we’ve been growing food intensively (since summer 2001) almost exclusively used a granular slow release mix. It wasn’t until last summer that we started playing with foliar feeding, and it was because we started applying other beneficial items to the orchard that we decided to mix it in for a burst of nutrients.

If you can handle the odor, a fish and seaweed emulsion is a great short-term addition (and fix) for plants that need a little pick me up (nutrient-deficient) especially in the early season when temperatures are cool.

Cold soils make for stagnant nutrients because the soil borne bacteria and fungi are only active in warmer soils (above 60F). So when we push our season and our plants look a little peaked (perhaps purple leaves like I often see on my earliest brassicas in early April under row cover) it’s more a reflection of those cooler soils being unable to supply the needed nutrients than a problem with the plant. Warmer weather always remediates this without any intervention. Although if this worries you, it would be a great time to implement some foliar feeding.

That being said, from all the research I’ve been doing foliar feeding is not really recommended by extension agencies, and being a master gardener, they are the experts I rely on for science-based gardening resources.

Stomata, the pores on leaves (like pores on our faces), are not meant to uptake nutrients; they are more designed for gas exchange. It does work to possibly right a nutrient deficiency but long-term you should always always be feeding your soil microbes. They are the true life-givers and literal foundation of our lives.

Containers vs In-Ground

If you grow in the ground, it’s a fair bit easier to fertilize. With containers, however, every time we water we are leeching a some nutrition out the pot and onto the deck or ground.

For container plants, I tend to plant in an even higher concentration of compost (30% compost to potting soil) and top dress the containers about once a month during the growing season with some slow release fertilizer.

Foliar feeding would also be an excellent choice for container grown tomatoes or peppers, for example, as they need a fair bit of nutrients to make the magic happen. For container gardens, I’d use foliar feeding (fish/seaweed emulsion) 1 tsp/gallon of water weekly once the plants start setting fruit.

Application Schedule

So what to use and when? I’ve put this together chart to help take the guessing work out of it for you this summer, and for years to come.

Get updated by email whenever there’s a new post

Comments

If you’re a subscriber, you can discuss this post in the forums

Leave a Reply